[ad_1]

People wear protective face masks outside at a shopping plaza in Edgewater New Jersey, on July 8, 2020.

Reuters

The ideal face mask for coronavirus protection blocks large droplets along with smaller airborne particles.

In general, masks should have more than one layer and be made of tightly woven fabrics.

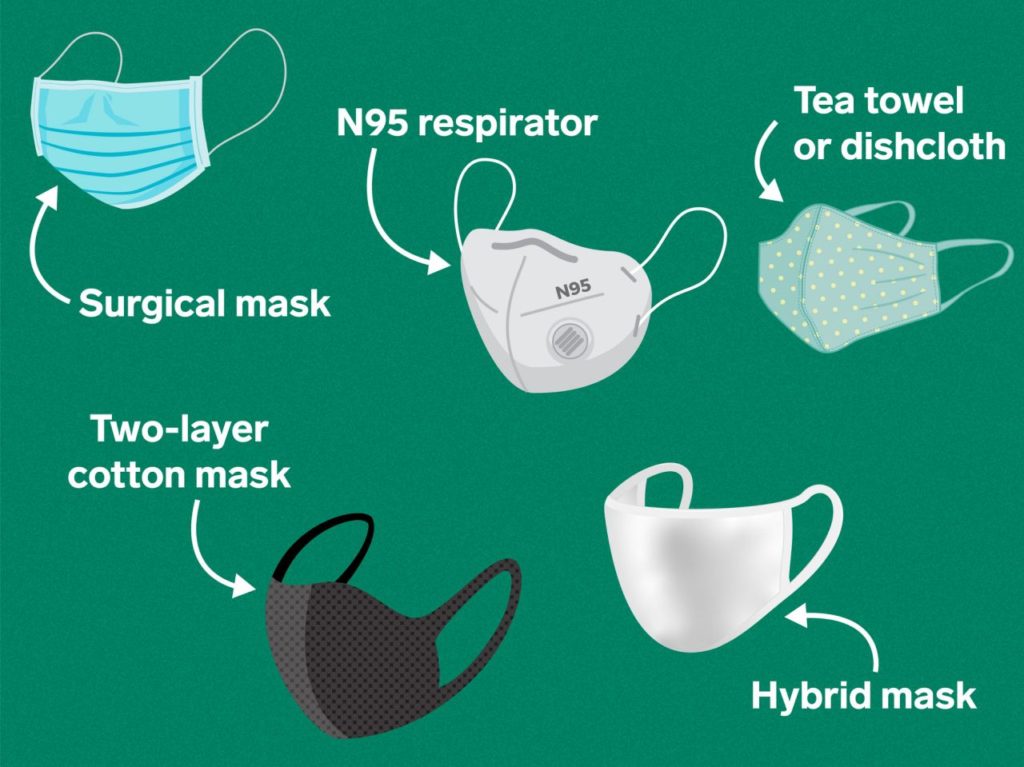

Based on several studies evaluating masks’ protection levels, we’ve ranked the most common types from best (an N95 mask) to worst (masks with a built-in valve or vent).

Visit Business Insider’s homepage for more stories.

A simple trick can reveal whether your face mask offers sufficient protection: Try blowing out a candle while wearing it. A good mask should prevent you from extinguishing the flame.

The rule isn’t foolproof, but it should help weed out masks that aren’t very protective.

Ever since the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention began recommending cloth masks for the general public in April, researchers have been evaluating the best materials for filtering the coronavirus. An ideal mask blocks both large respiratory droplets from coughs or sneezes — the primary method by which people pass the virus to others — along with smaller airborne particles called aerosols, which are produced when people talk or exhale.

It should be sealed around the nose and mouth, since any gaps, holes, or vents could allow droplets to leak out and potentially infect another person.

Assuming masks are worn properly, certain materials consistently perform better than others in studies. Based on the latest research, here’s a ranking of the best and worst face coverings:

Yuqing Liu/Business Insider

‘Hybrid’ masks are among the safest homemade options

As a general rule, mask fabrics should be woven as tightly as possible. That’s why fabrics with higher thread counts are better at filtering particles.

It’s also preferable to have more than one layer. The World Health Organizations recommends that fabric masks have three layers: an inner layer that absorbs, a middle layer that filters, and an outer layer made from a nonabsorbent material like polyester.

N95 masks are the most protective because they seal tightly around the nose and mouth so that very few viral particles seep in or out. They also contain tangled fibers to filter airborne pathogens — the name refers to their minimum 95% efficiency at filtering aerosols. A recent Duke study showed that less than 0.1% of droplets were transmitted through an N95 mask while the wearer was speaking.

Story continues

That’s why they’re generally reserved for healthcare workers.

Disposable surgical masks are also made of non-woven fabric. A 2013 study found that surgical masks were about three times as effective at blocking influenza aerosols than homemade face masks (that was true, at least, when air flow was slower than a cough but faster than a human breathing during light work).

Still, there are homemade options that come close to the level of protection of an N95 or surgical mask.

Packaged surgical face masks.

InkheartX/Shutterstock

An April study from the University of Chicago determined that “hybrid” masks — combining two layers of 600-thread-count cotton paired with another material like silk, chiffon, or flannel — filter at least 94% of small particles (less than 300 nanometers) and at least 96% of larger particles (bigger than 300 nanometers). Two layers of 600-thread-count cotton offer a similar level of protection against larger particles, but they weren’t as effective at filtering aerosols.

That study, however, conducted measurements at low air-flow rates, so the masks might offer less protection against a cough or sneeze. Still, multiple layers of high-thread-count cotton are preferable to face coverings made from a dishcloth or cotton T-shirt.

Fabrics like silk or cotton have more variable performances

A June study published in the Journal of Hospital Infection found that masks made from vacuum-cleaner bags were among the most effective alternatives to surgical masks, followed by masks made from tea towels, pillowcases, silk, and 100% cotton T-shirts, respectively.

A woman sews hospital masks at the Detroit Sewn facility in Pontiac, Michigan, on March 23, 2020.

Rebecca Cook/Reuters

Research from the University of Illinois, meanwhile, found that a brand-new dishcloth was slightly more effective than a used 100% cotton T-shirt at filtering droplets when a person coughs, sneezes, or talks. That study (which is still awaiting peer review) also found that a used shirt made of 100% silk was more effective at filtering high-momentum droplets, likely because silk has electrostatic properties that can help trap smaller viral particles.

The University of Chicago study came to a different conclusion, however: Those researchers found that a single layer of natural silk filtered just 54% of small particles and 56% of larger particles. By contrast, four layers of natural silk filtered 86% of small particles and 88% of large particles at low air-flow rates.

Bandanas and scarves don’t offer great protectionKevin Houston uses a bandana to cover his face on April 23, 2020, in Evanston, Illinois.

Stacey Wescott/Chicago Tribune/Tribune News Service/Getty Images

Bandanas and scarves have performed poorly in multiple studies.

The Journal of Hospital Infection study found that a scarf only reduced a person’s infection risk by 44% after they shared a room with an infected person for 30 seconds. After 20 minutes of exposure, the scarf only reduced infection risk by 24%.

Similarly, the Duke researchers found that bandanas reduced the rate of droplet transmission by a factor of two, which makes them less protective than most other materials.

For the most part, though, any mask is better than no mask, with one notable exception: The CDC cautions people not to wear masks with built-in valves or vents.

Masks with one-way valves can expel infectious particles into the atmosphere, helping to fuel transmission.

Mask studies should be taken with a grain of salt

Although research is coalescing around the idea that a few types of masks offer the best protection, it’s not always easy to simulate how a mask will perform in real life.

That’s because only some tests directly mimic the size of novel coronavirus particles, while others evaluate performance based on viruses like influenza. Researchers also still aren’t sure about the degree to which the virus gets transmitted via aerosols, since those tiny particles are extremely hard to trap and study without killing the virus. Some scientists even have different ideas of what constitutes an aerosol — the generally accepted cutoff is less than 5 microns (that’s roughly the size of a dust particle) — and many experts think the delineation is arbitrary altogether.

Different studies also test masks under different circumstances: Some mimic the heavy air flow produced when a person coughs, while others mimic the air flow when a person is talking or breathing normally.

And of course, masks perform differently depending on how they’re worn. That’s why it’s better to stick with more protection over less.

Read the original article on Business Insider

[ad_2]

Source link