[ad_1]

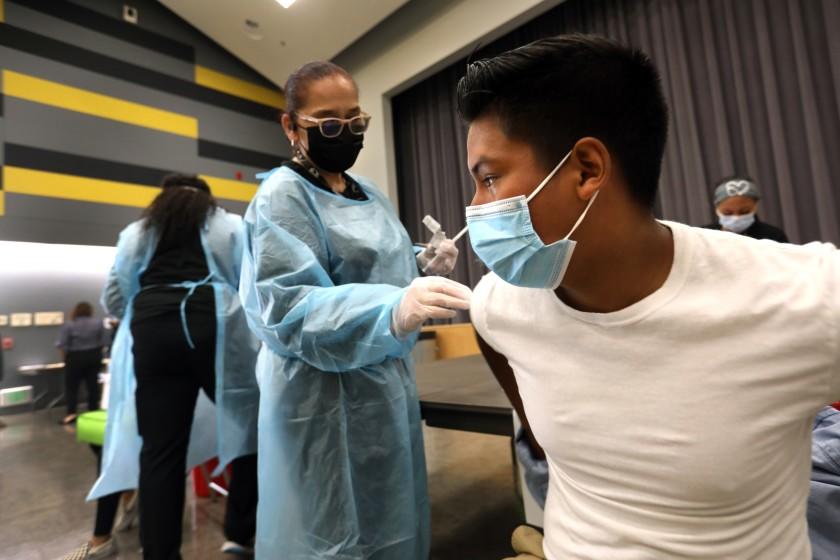

D’Marco Ahumada, age 16, gets his first dose of COVID-19 vaccine at San Pedro High School. A new report from the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention says coronavirus infections in vaccinated people are extremely rare, and very few result in death. (Carolyn Cole/Los Angeles Times)

In a four-month span during which the U.S. vaccination campaign was in a race against a spate of COVID-19 surges, a nationwide study has found that roughly 10,000 people became infected with the coronavirus after they had received all their recommended doses.

Two percent of those patients with “breakthrough” infections died, according to a new report from the Centers for Disease Control & Prevention.

That may sound like bad news. But run the numbers, and infectious-disease experts say it is actually quite good news indeed.

Between Jan. 1 and April 30, a total of 10,262 post-vaccination infections were reported by 46 states and territories. Those cases represent less than 0.01% of the 107,496,325 people in the U.S. who had been fully vaccinated by April 30, according to the CDC’s COVID Data Tracker.

Vanderbilt infectious-disease expert Dr. William Schaffner calls the new findings a report card on the three COVID-19 vaccines — the two-dose offerings from Pfizer-BioNTech and Moderna and the single-shot option from Johnson & Johnson — rolled out so far in the United States. He’s not among the new report’s authors. But he’s a pretty proud uncle.

“It gives them an A, if not an A-plus,” Schaffner said. “It shows that infections among vaccinated people are, first of all, unusual. And second, that there are very few among these infections that are linked to deaths.”

In the report released Tuesday, the CDC researchers acknowledge that their tally of 10,262 breakthrough infections is likely a “substantial undercount.” Many people who became infected despite getting vaccinated probably experienced mild illness at worst and didn’t seek out testing to confirm the cause.

Even so, the number of COVID-19 infections that were prevented by vaccines “will far exceed” the true number of post-vaccine infections, the study authors wrote in the Morbidity and Mortality Weekly Report.

The study also found that 995 people who had received all their recommended doses were known to have been admitted to a hospital. But not all of them went there because of COVID-19 — in fact, 29% had no COVID-19 symptoms and were admitted for other reasons.

Story continues

In all, 160 fully vaccinated people with a breakthrough infection died during the study period. That’s 2% of those with breakthrough infections, and 0.0001% of U.S. residents who were fully vaccinated by April 30. All 160 people were between the ages of 71 and 89.

The states reporting their deaths certified only that those patients were infected with coronavirus — not that they had died as a result of COVID-19. In some cases, it’s possible that another ailment was responsible for their death.

In short, while the COVID-19 vaccines authorized for use in the U.S. have not been an impregnable shield against infection, they have performed remarkably well, experts said. Even when breakthrough infections occurred, the vaccines likely prevented severe disease, hospitalizations and deaths in those who got them.

“This is very reassuring,” said Dr. Paul Offit, a vaccine expert at Children’s Hospital of Philadelphia. As the proportion of vaccinated and recovered Americans rises, infections should continue their steep decline, he added.

Further reassurance came from another of the report’s findings: that breakthrough infections did not appear more likely to stem from the coronavirus variants that have raised concerns among scientists.

Studies have hinted that genetic variants that arose in the United Kingdom, Brazil, South Africa and the U.S. could erode the effectiveness of vaccines. But the prevalence of “variants of concern” among those who suffered a breakthrough infection did not suggest that any one variant was doing so in dramatic fashion.

In all, 5% of the samples taken from patients with known breakthrough infections were genetically sequenced, and 64% of them turned out be variants of concern.

Their diversity within this group tracked closely with their presence in the general U.S. population: the UK variant (known to scientists as B.1.1.7) was most common, followed by two variants that were first detected in California (B.1.429 and B.1.427). Two others, Brazil (P. 1) and South Africa (B.1.351), brought up the rear.

“That tells me the vaccines are preventing infections and there are no rogue elements out there evading that protection,” Schaffner said. “The vaccines are working.”

But that doesn’t mean we can afford to rest on our laurels.

“It’s a great report card today, but you know we have another semester coming,” Schaffner added. “We will be looking forward to see how long vaccines’ protection lasts. And we have to keep monitoring for those variants. We must remain on alert.”

This story originally appeared in Los Angeles Times.

[ad_2]

Source link